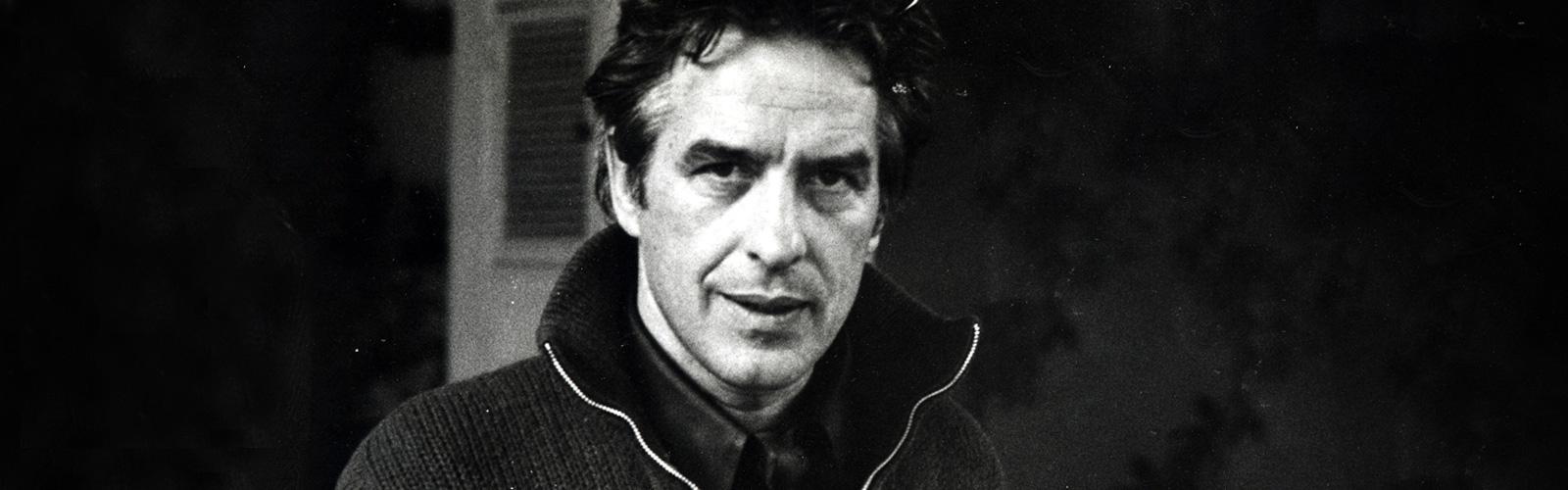

Cassavetes is an actor ans director who was born on December 9, 1929, in New York City.

Even though he’s better known to most people as an actor, John Cassavetes’ true artistic legacy derives from his work behind the camera as a director. Cassavetes was America’s first truly independent filmmaker, an iconoclastic maverick whose movies challenged the assumptions of the cinematic form. Obsessed with bringing to the screen the “small feelings” he believed that American society at large attempted to suppress, Cassavetes’ work emphasized his actors above all else, favoring character examination over traditional narrative storytelling to explore the realities of the human condition. A pioneer of self-financing and self-distribution, he led the way for filmmakers to break free of Hollywood control, perfecting an improvisational, cinéma vérité aesthetic all his own.

John Cassavetes was born in New York on Dec 9, 1929. He was the son of Greek immigrants. After attending public school on Long Island, he later studied English at both Mohawk College and Colgate University prior to enrolling at the New York Academy of Dramatic Arts. Upon graduating in 1950, he signed on with a Rhode Island stock company while attempting to land roles on Broadway and made his film debut in Gregory Ratoff’s Taxi in 1953. A series of television roles followed, with Cassavetes frequently typecast as a troubled youth. By 1955, he was playing similar parts in the movies, appearing in pictures ranging from Night Holds Terror to Crime in the Streets.

Cassavetes’ career as a filmmaker began most unexpectedly. In 1957, Cassavetes was appearing on a New York-based radio show called Night People to promote his recent performance in the film Edge of the City. While talking with host Jean Shepherd, Cassavetes commented that he felt the film was a disappointment and claimed he could make a better movie himself. At the close of the program he asked listeners interested in an alternative to Hollywood formulas to send in a dollar or two to fund his aspirations, promising he would make “a movie about people.” No one was more surprised than Cassavetes himself when, over the course of the next several days, the radio station received over 2,000 dollars in dollar bills and loose change. True to his word, he began production within the week, despite having no idea exactly what kind of film he wanted to make.

Cassavetes began work on what was later titled Shadows using a group of students from his acting workshop. The production had no script or professional crew, only rented lights and a 16 mm camera. Without any prior experience behind the camera, Cassavetes and his cast made mistake after mistake, resulting in a soundtrack which rendered the actors’ dialogue completely inaudible. A sprawling, wholly improvised piece about a family of black Greenwich Village jazz musicians — the oldest brother dark-skinned, the younger brother and sister light enough to pass for white — the film staked out the kind of fringe society to which Cassavetes’ work would consistently return, posing difficult questions about love and identity.

The finished verson of Shadows appeared in 1960 and was hailed as a groundbreaking accomplishment receiving the Critics Award at that year’s Venice Film Festival. After failing to find a local distributor in the US the movie finally was released in the US with the backing of a British distributor. Because of the success of Shadows Paramount hired Cassavetes to direct the 1961 drama Too Late Blues with Bobby Darin. The movie was a financial and critical disaster, and he was quickly dropped from his contract. Landing at United Artists, he directed A Child Is Waiting for producer Stanley Kramer. After the two men had a falling out, Cassavetes was removed from the project, which Kramer then drastically re-cut, prompting a bitter Cassavetes to wash his hands of the finished product.

“We don’t take the time to be

vulnerable with each other”

Stung by his experiences as a Hollywood filmmaker, he vowed to thereafter finance and control his own work, turning away from directing for several years to earn the money necessary to fund his endeavors. A string of acting jobs in films ranging from Don Siegel’s The Killers to Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby to Robert Aldrich’s The Dirty Dozen (for which he received an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor) wrapped up Cassavetes for all of the mid-’60s, but in 1968 he returned to filmmaking with Faces, the first of his pictures to star his wife, the brilliant actress Gena Rowlands. Another edgy drama shot in Cassavetes’ trademark cinéma vérité style, Faces was a tremendous financial and critical success, garnering a pair of Oscar nominations as well as winning five awards at the Venice Film Festival; its success again brought Hollywood calling, but this time the director entertained only those offers affording him absolute creative control and final cut.

After coming to terms with Columbia, Cassavetes began work on 1970’s Husbands, which co-starred Peter Falk and Ben Gazzara. After helming 1971’s Minnie and Moskowitz for Universal, he turned to self-financing, creating his masterpiece A Woman Under the Influence, which earned Rowlands an Academy Award nomination in the Best Actress category. With a story he developed with longtime fan Martin Scorsese, Cassavetes next turned to 1976’s film noir The Killing of a Chinese Bookie; though also reissued two years later in a truncated version, the picture failed to find an audience and was barely even circulated. When the same fate befell 1978’s Opening Night, Cassavetes was forced to return to Columbia in 1980 to make Gloria.

Four years passed before the director’s next film, Love Streams. His subsequent effort was 1985’s aptly titled Big Trouble, a comedy already in production when Cassavetes took over for writer/director Andrew Bergman, who had abruptly quit the project. The finished film was subsequently recut by its producers, and Cassavetes publicly declared it a disaster. Upon completing the picture, he became ill; regardless, he continued working, turning to the theatrical stage when he could no longer find funding for his films. A Woman of Mystery, a three-act play which was his final fully realized work, premiered in Los Angeles in 1987. On February 3, 1989, John Cassavetes died. Son Nick continued in his father’s footsteps, working as an actor as well as the director of the films Unhook the Stars (1996) and She’s So Lovely (1997), the latter an adaptation of one of his father’s unfilmed screenplays.

What did John Cassavetes think about his Greek heritage?

This excerpt is from a paper written by Vrasidas Karalis “John Cassavetes and the Uneasy Conformism of the American Middle Class“:

In September 1981, as I opened the door of my home in Piraeus, Greece, I came face to face with none other but John Cassavetes. It was early in the morning and I was heading to the university for exams.

In broken Greek, Cassavetes told me that he was looking for the house where he spent some years of his childhood in the early thirties before moving to New

York for good. “We lived in Larissa,” he said, “but we stayed here for some years before taking the boat to America, to Long Island, if you know.” Of course, the house was not there anymore. It had been demolished in the sixties…

…As he was leaving, he said: “Eucharisto poly. I am so sorry I have forgotten my Greek.” And added: “My father who died recently spoke very good Greek till the last day of his life, although he had gone to New York very young.” And

he drove off discretely.

In another article John talks about his wife actress Gena Rowlands:

“Gena’s learning Greek,” said John as he crawled out from under the coffee table.” John, whose father owns a steamship company, is of Greek parentage and learned to speak the language as a young boy. Before we could ask why Gena had decided to learn Greek, the two of them were off on an imitation of the Cassavetes Steamship radio commercial, whooshing and puffing away like a pair of crazy tug boats. A little winded from all the exertion, Gena went on to explain about learning Greek.

“John speaks it,” she said, “so I figured I could too. Besides it’s wonderful when we’re out in a crowd and want to get away. You can’t go ‘Pssst!’ Everybody looks at you and they know what that means. But I can just say, ‘Let’s scram!’ in Greek to John and nobody understands.”